When I decided to enter military service, my Dad, a World War II veteran, told me, "This will change you in ways you can't possibly understand until you've been through it." He was right, as he often was, but some of those changes came as a surprise even to me, who grew up listening to war and sea stories from my Dad and my uncles. The difference, by the way, between a fairy tale and a war story is that a fairy tale begins "Once upon a time," while a war story begins "No s**t, there I was..." We veterans all know the difference, having told our share of stories, some of which may have even been true.

There are, of course, things that those who belong to what beloved WW2 military cartoonist Bill Mauldin once described as the "benevolent and protective brotherhood of them what has been shot at" have in common, some of which civilians just don't get. So, without further ado, here are five examples.

Bad knees and back pain.

My service was during the last years of the Cold War, when the standard-issue field pack was the venerable old ALICE pack, with its minimal aluminum frame made by the lowest bidder. We also had the old Vietnam-era black boots, which at least took a decent shine but were, again, made by the lowest bidder; I remember that back in the day those boots went for about five bucks in surplus stores, which is about $4.95 more than they were worth. Long road marches usually turned into a competition between your feet and your back as to which would cause you the most trouble, and the occasional ruck run, with or without weapons, just made things worse. As evidence of this, just walk into any Veterans of Foreign Wars hall, play the National Anthem, and listen to the cracking and popping of knees and spines as all the old vets scramble to their feet.

A chronic need to always have dry socks and ranger candy (extra-strength Tylenol) close at hand.

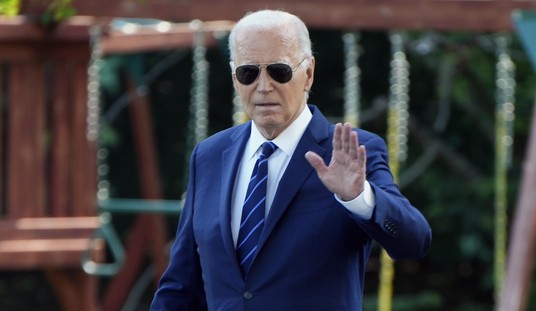

The first item in this list leads to the second; one way to spot a veteran is to look in their dresser to see abundant socks, all neatly rolled and folded into little GI "boats," and then look around for a big bottle of extra-strength Tylenol, known by the troops as "ranger candy." No field exercise or road march would be attempted without these items, and with good reason; if soldiers know anything, they know how to take care of their feet, as all too often they were our only mode of transportation. The Tylenol? Those were to deal with the effects of our boots and ALICE packs. Among veterans, tall tales and dry socks go together like Joe Biden and dementia.

See Related: Biden Descends Into Confusion About Jan. 6, Tells Wild Tales About Trump at Michael Douglas Fundraiser

Being able to sleep anywhere, in any position.

During basic training, we were frequently shuttled around from training area to training area in semi-trailers that were, essentially, just cargo trailers with crude wooden benches on the sides and in the center. These were coated in unpainted, shiny metal and, while the drill sergeants insisted we call them "Silversides," we invariably called them "cattle trucks," because we were certain that was what they had been before being adapted for soldiers. Returning from a night exercise, the company was short one truck that had broken down en route to us, resulting in packing four platoons of troops into three platoon's worth of trailers, so I ended up on my feet, holding on to a pipe that was part of the center row of benches, and managed to fall asleep, standing, with my M16 cradled in my arms and my old steel helmet pulled down over my eyes. Soldiers develop this skill very rapidly; some years later, I spent my first night in Saudi Arabia, hours after getting off the plane, in a 2 1/2 ton trailer, with my Kevlar helmet for a pillow. "Never walk when you can stand, never stand when you can sit, never sit when you can lie down, and never be awake when you could be asleep" is a truism in the military for a reason, and an old soldier is marked by the ability to fall asleep anywhere in any position.

Scars that we brag about.

My best one is from a pre-military incident, in which a 12-gauge at a range of about three feet took a bite out of my leg; call it a minor difference of opinion. But I have my share of scars and in any gathering of old veterans, it's only a matter of time before they start rolling up sleeves, pulling up pant legs, or unticking shirts to point at a scar and saying, "Oh, yeah? Well, let me tell you about the time I got this." Two of my uncles had such scars, one from a Japanese bayonet on Iwo Jima, the other a whole array of scars on his head and neck from fragments of a German 88mm shell. They are points of pride, as important as the shiny little bits of ribbon that we all hang on our "I love me" walls with the rest of our memorabilia. Nowadays I understand some of these scars may be due to "gender-affirming surgeries," but those just don't carry the same brag potential.

See Related: SHOCKER: DOD Prompting Gender Confusion in Military Kids

Tinnitus.

Spending a good part of your life around diesel engines, helicopters, firing ranges and artillery isn't good for one's hearing. I even have physical evidence of this, in the form of a letter from the Veteran's Administration documenting my 10% disability rating for hearing loss, but the term "hearing loss" doesn't cover the constant buzzing from my left ear, which began on a late-night field exercise when a grenade simulator bounced out of a pyro pit and detonated about ten feet away from me. Living as I do now in a place where mosquitoes are a concern, tinnitus leads to a lot of false alarms; visitors will sometimes wonder why I stop in mid-stride and start waving my hands around my head when there are no mosquitoes in evidence.

There are, of course, many more such examples, and every veteran (or family member of a veteran) can probably add a few to the list. But these things are inescapable reminders of our service; they stay with us for life and are often passed down in the form of the tales we tell the younger generations. I have six grandchildren myself, and as they go through their lives, I expect they will tell people of how they once, on Grandpa's knee, heard him spill a story that began, "No s**t, there I was..."

Got any examples of your own? The comments are yours!